Welcome to what will be my final post of 2022. Now that I’ve been at this a while, the pace of my revelations has slowed somewhat, but I’m still learning new things all the time. Sometimes I think might skip posting for a month, but then I happen upon something that interests me and I want to share. This happened recently with a couple articles from the New York Times. One, “They Fought the Law. And the Lawn Lost,” describes a Maryland couple’s fight against their homeowners’ association over their pollinator garden. Guess what happened? The second, “The Climate Impact of Your Neighborhood, Mapped,” isn’t about gardening at all, but is germane to my interests, and possibly yours too.

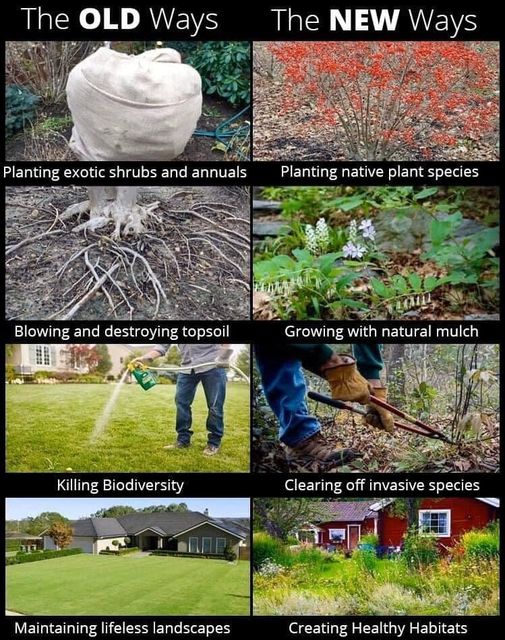

Because you might not be able to read the article without a subscription, here’s a quick summary. Janet and Jeffrey Crouch began planting a pollinator garden in their suburban front yard in the early 2000’s. They live in Beech Creek, outside of Columbia, Maryland. In 2012, their next-door neighbor began complaining. He couldn’t “enjoy his own property, he wrote, due to the ‘mess of a jungle’ next door.” Nancy Lawson, who blogs as the Humane Gardener and is Janet Crouch’s sister, says the HOA’s letter criticized the “plantings which grow back every year.” The HOA demanded the Crouches yank out their garden and plant grass, so they sued. The HOA countersued. Ultimately, this led to the passage of a state law prohibiting Maryland HOAs from restricting “low-impact landscaping”: rain gardens, pollinator gardens, xeriscaping, and the like. Yay!

Text of the bill: https://legiscan.com/MD/text/HB322/2021

Read Lawson’s play-by-play about the fight here.

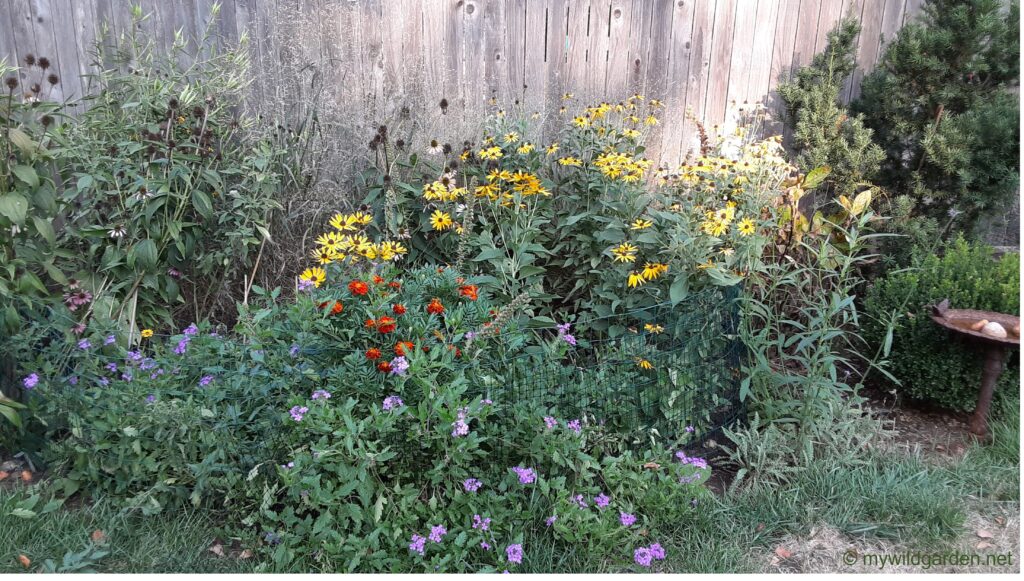

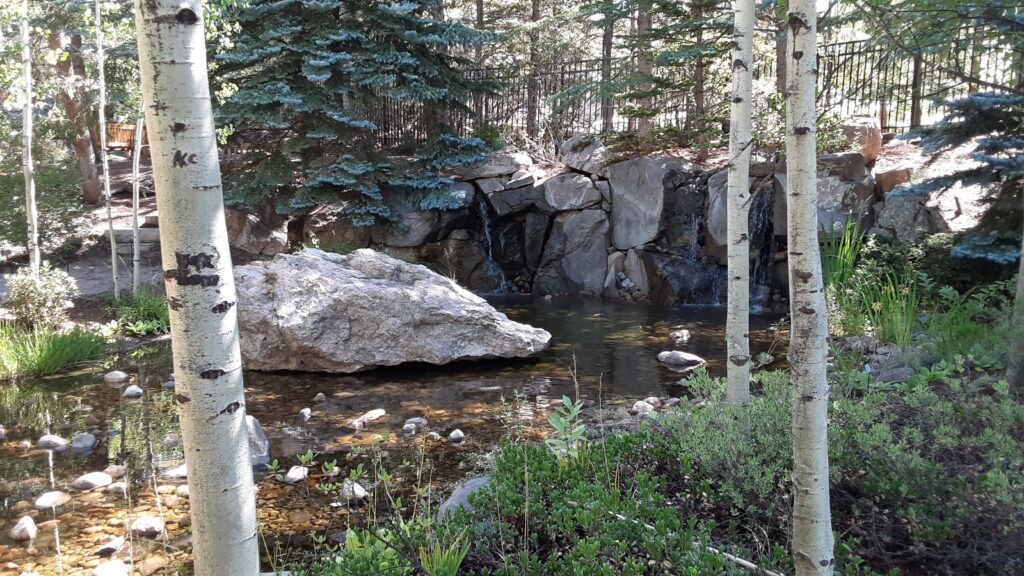

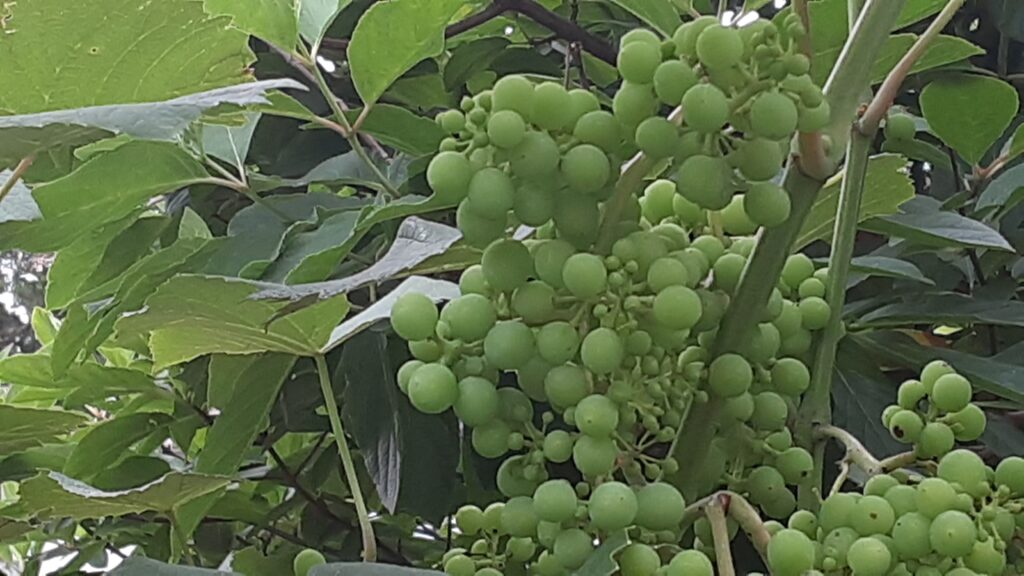

One thought. Pollinator gardens are not going to appeal to everyone, as the Crouches’ experience shows. As this image of their delightful yard shows, they’ve incorporated many cues to care: clearly delineated beds, layered plantings, mowed paths. I continue to hope that the best way to persuade people to stop using chemicals is by showing them alternatives they find attractive, but most people like what they’re familiar with. The passage of this bill is an important step, and gives gardeners arguments to build on if they need to step things up.

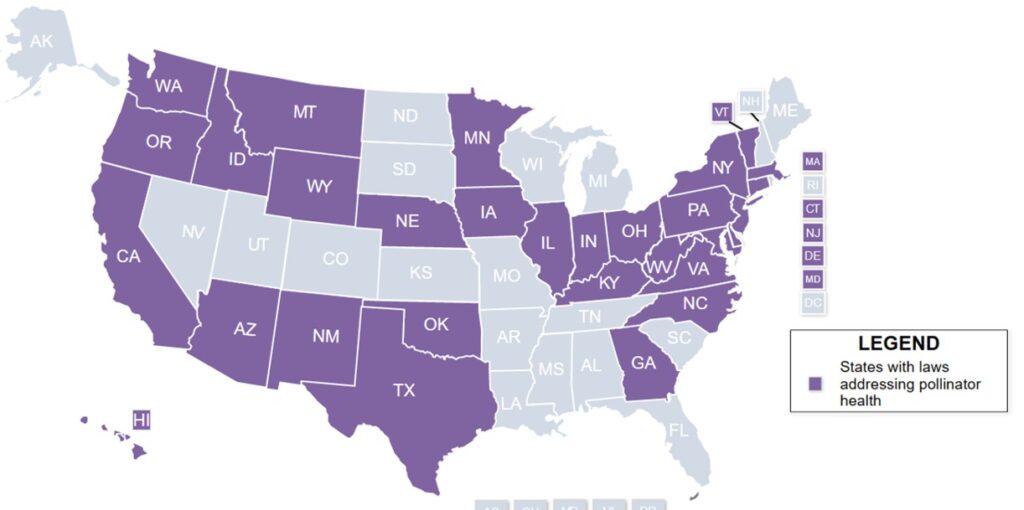

How many states have passed laws like these? Sixteen, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures’ Pollinator Health page.

Dozens of states have passed legislation to promote the health of pollinators, which include bees, wasps, bats and butterflies.

Are Kansas and Missouri included among these dozens? No. States that have “enacted legislation or adopted resolutions related to pollinator health” include California, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, and Washington. “Legislation related to pollinator health” can include anything from banning pesticides to naming an official state pollinator (Texas), or creating special pollinator license plates.

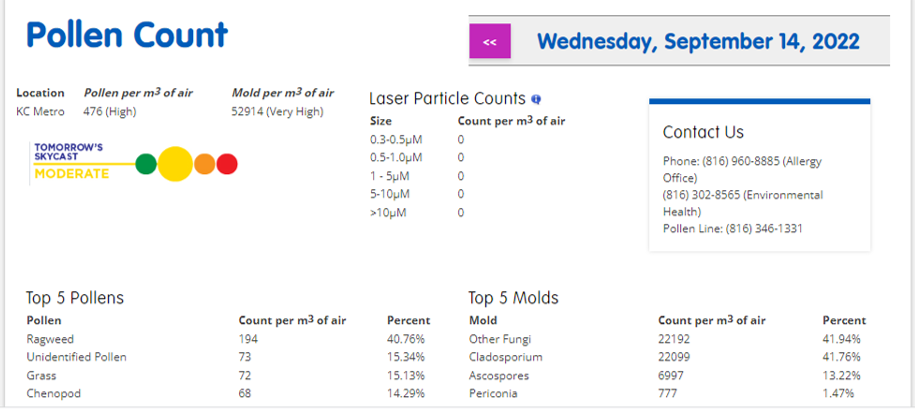

Would you look at this image? A white band of apathy spreads across the Midwest, where we find the largest concentration of neonicotinoids, a particularly harmful insecticide widely used in field crops (soybean, cotton, canola, wheat, sunflower, potato, and many vegetables). Neonics may also be found in ornamentals sold by retailers, although this article says large stores like Walmart, True Value, Lowe’s, and Home Depot began phasing out their use in 2017. This article from a Salem, Oregon newspaper does a good job explaining the impact of neonicotinoids, and how to avoid using them.

Neonics have been banned in the EU, Canada, and some states, and in the US a nation-wide ban has been proposed. That seems more significant than having special license plates, but like signs in yards, these can help raise awareness. I imagine that many people who are inclined to feel positively about pollinators still spread Bug Blaster on their lawns. They just haven’t thought about it. Although we have lots of specialty license plates in Kansas and Missouri, I don’t see one advocating for pollinators. Maybe some of you will be inspired to write your legislator.

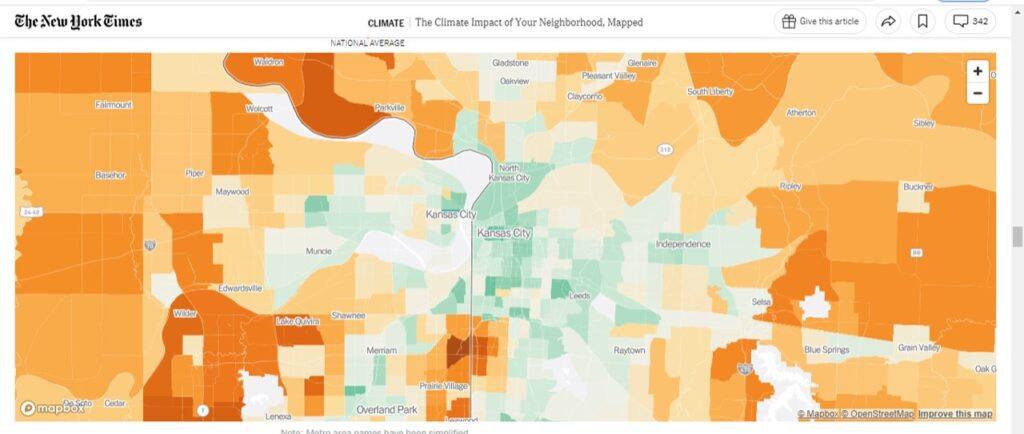

The second article of interest, sobering but interesting, concerns the Climate Impact of Your Neighborhood.

Researchers have discovered that dense inner-city neighborhoods have the lowest emissions per household. They’re green on the map.

“Households in denser neighborhoods close to city centers tend to be responsible for fewer planet-warming greenhouse gases, on average, than households in the rest of the country. Residents in these areas typically drive less because jobs and stores are nearby and they can more easily walk, bike or take public transit. And they’re more likely to live in smaller homes or apartments that require less energy to heat and cool.

Emission rates are much higher in the suburbs. Bigger houses require more energy to heat and cool. Residents drive longer distances, and have more of everything—electronics, appliances, vehicles.

The maps aren’t based on emissions but consumption, a combination of electricity use, driving, income levels, and more. It’s one measurement where we don’t want to be above average, but we are. If you look at the map, you can tell exactly where your neighborhood fits on this scale. This information may Influence individual choices to recycle, walk or ride bikes, things like that. It may also influence policy makers.

With that thought, I’ll conclude this final post of year I’ll be back in mid-January. In the meantime, enjoy the holidays, and thanks for reading!

REFERENCES

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/14/climate/native-plants-lawns-homeowners.html

https://www.ncsl.org/research/environment-and-natural-resources/pollinator-health.aspx

https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/4079?s=1&r=39

https://www.motherearthnews.com/organic-gardening/neonicotinoid-insecticides-zmgz14fmzsto/