Last weekend I was in Houston for a friend’s memorial service. While there, I toured the gardens at Bayou Bend.

These are the opposite of a wild garden, very formal and completely delightful—most of the time. How did they look after February’s arctic freeze? Not so good by some measures, but also not too bad, considering.

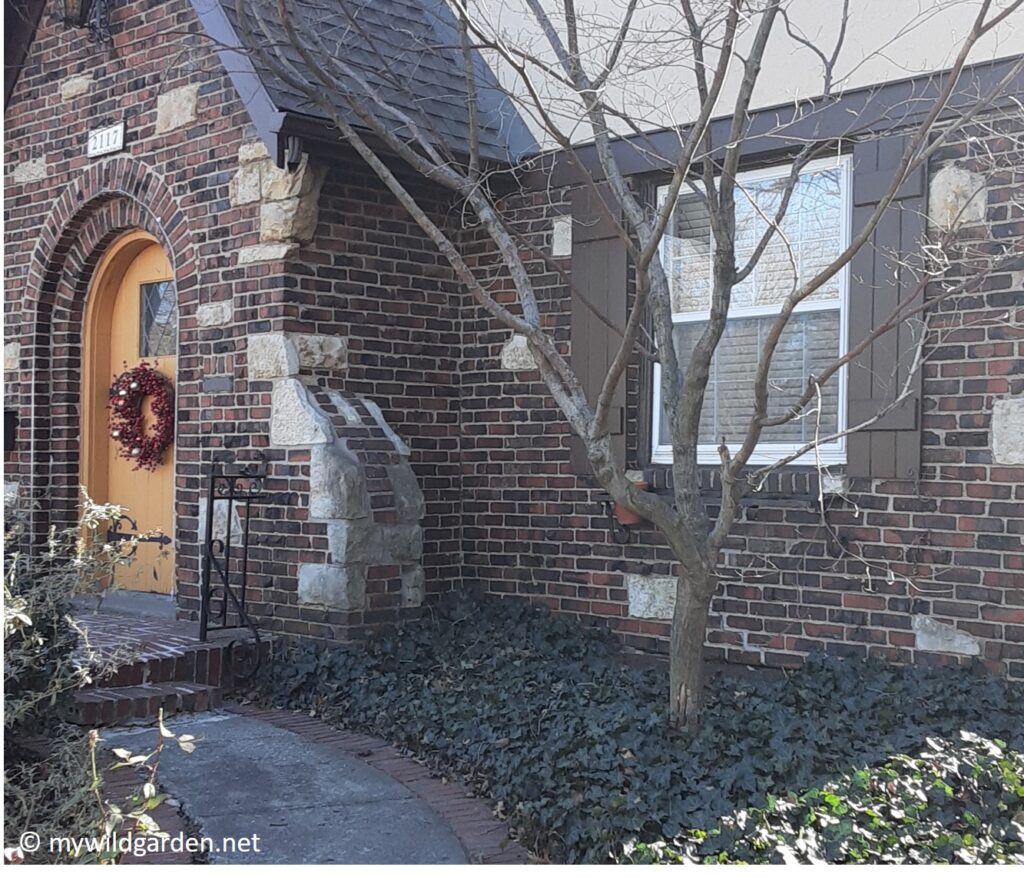

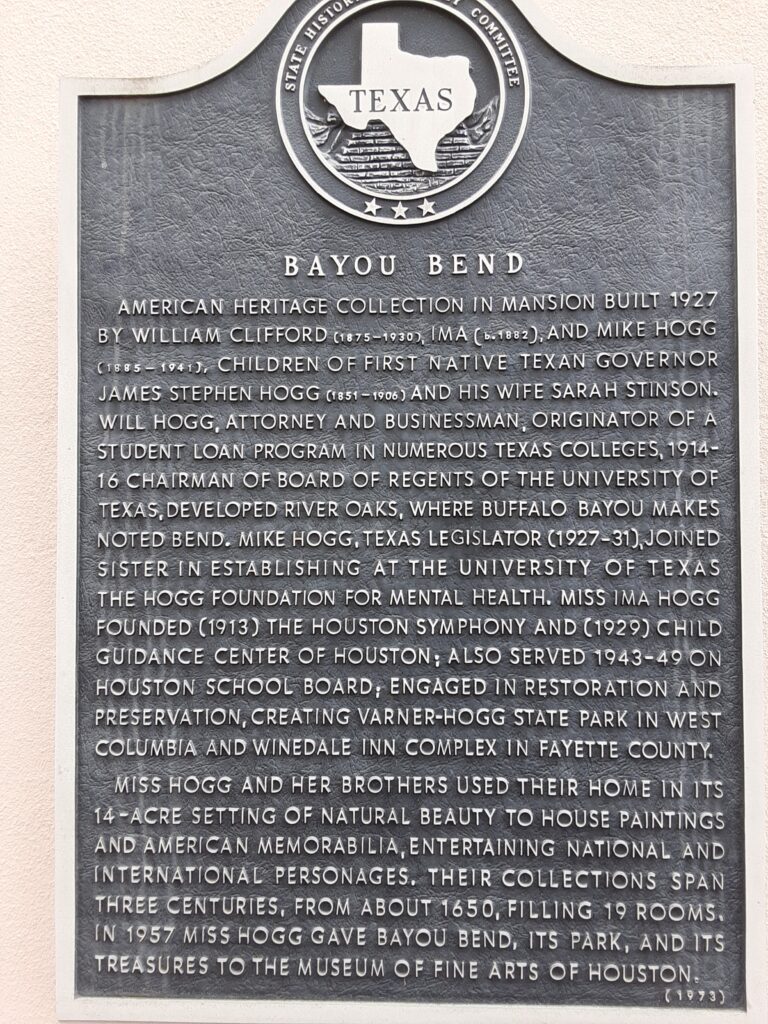

Houston does have an arboretum that emphasizes native planting—kind of like Powell Gardens meets the Lakeside Nature Center—but that’s where the service was, so I was eager to see something different. Bayou Bend is the estate and gardens of the unfortunately named Ima Hogg, an Adele Hall-type who poured her energies and fortune into worthwhile projects for the citizens of Houston. To enter, visitors cross a footbridge high above the sluggish, dirt-colored Buffalo Bayou.

It took a lot of creativity and imagination to envision this as the site of anything—estate, garden, or city. But lo and behold, look what a little imagination can do.

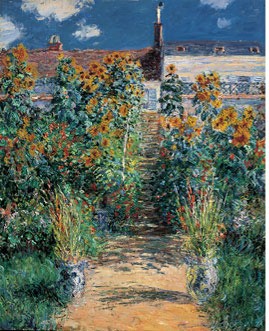

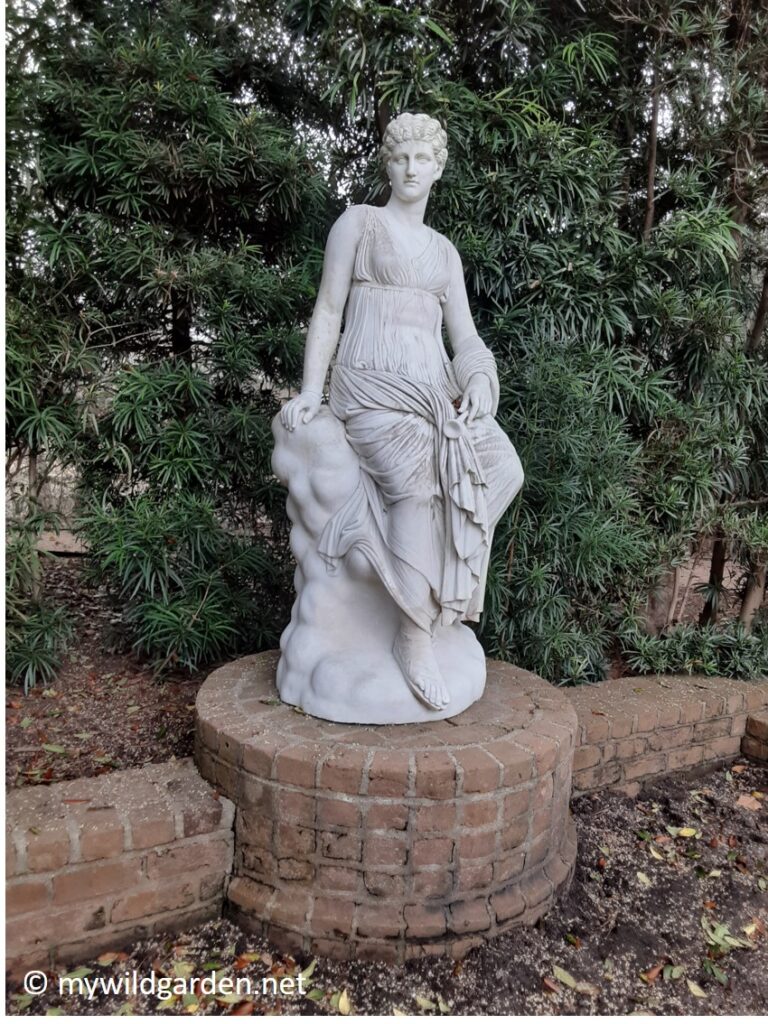

The mansion houses a premier collection of early American decorative arts, displayed in period rooms. The grounds cover fourteen acres, eleven “rooms” surrounded by woods. There is a pleasing contrast between the wild areas and the formal gardens, four of which are named for goddesses or muses. Visitors enter through Clio garden, where the Muse of History herself looks out from the center of a parterre, a formal circle of boxwood-lined beds that contain plantings of azaleas. No doubt these are stunning when in bloom. Here is a historic photo, and the way they looked on February 28, 2021.

Even in their dormant state, the plantings make a pleasant impression.

The house looks out over a lawn and stunning garden named for Diana, goddess of the hunt. The mobile tour says this garden was built in 1939 to host a meeting of the Garden Club of America.

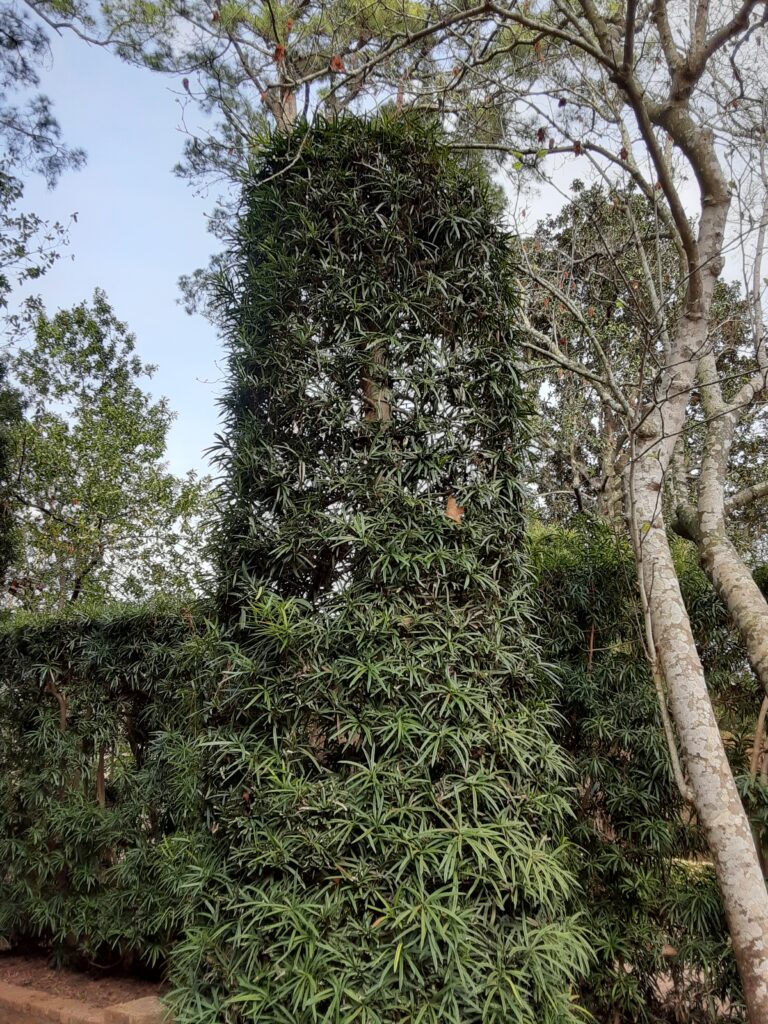

The statue of Diana stands out against “walls of evergreen yaupon hedges,” a type of holly, but the Japanese yews (Podocarpus macrophyllus) clipped into columns are what stand out to me.

The East Garden lawn is lined with low boxwoods clipped into S’s. All the edging is brick pavers. The fountain wasn’t working on the day I visited.

The azaleas in the East Garden were among first to be introduced to Houston. According to the tour, Ms Hogg helped popularize them in the 1930’s. A time when they were unfamiliar is hard to imagine, as they are ubiquitous now. The River Oaks Garden Club’s annual garden tour is called the Azalea Trail. Normally it would be held this week, but because of COVID, the next tour has been pushed back until 2022—a stroke of luck, given the state of the gardens this year.

From a distance, the rust-colored foliage of the frozen azaleas resembles blooms.

Some might be interested to see the environment where Bayou Bend is located. It is not a typical neighborhood. Here is a peek through the fence at the next-door neighbor’s house.

Is that work by Louise Bourgeois and Magdalena Abakanowicz?

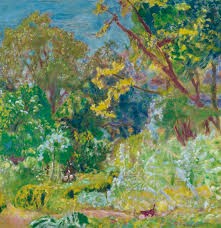

A walk through woods on winding paths brings visitors to a garden named for Euterpe, the muse of poetry and music. Nearby are two remarkable trees, both older than the house, an American sycamore estimated to be 150-200 years old, and a loblolly that’s about 150 years old. (I didn’t get a picture of the loblolly, but it is big.)

I think it’s interesting that Bayou Bend doesn’t seem to showcase any of the spectacular Live Oak trees Houston is famous for. (You can get an idea of the sculptural quality of these trees from the photo of the neighbor’s house.)

Although most of this year’s flowers may be casualties of the freeze, I suspect that the majority of the azalea bushes will be okay. If they’re not, they’ll be replaced. That’s the way Houston is. It’s nothing if not resilient–I can go on and on about the place and its can-do character. The fact that city exists at all is a testament to people’s imagination and will (and wealth).

Even though many people there are still without power and water, Houston is getting on with the business of being Houston. As I was leaving, I noticed crews of workers digging up and replacing the dead annuals in front of my hotel, while tiny leaves sprouting on the trees made a green mist on the horizon. At Bayou Bend, although the damage is no doubt extensive, some of this year’s azaleas are determined to bloom–like these.