During gardening season I’m so focused on the plants at ground level, I sometimes forget to notice trees. They’re like power lines, seen but not seen. I like it when the leaves fall, exposing their sculptural shapes..

Kansas City trees: some history

Obviously, trees do well here. I’ve heard that mature trees are so effective at lowering temperature, some old neighborhoods are in different USDA hardiness zones than new ones. Out in the country trees grow in brushy tangles along fence lines or in wide, dark strips beside creeks and rivers. It’s hard to imagine that, before Lewis and Clark’s day, this region was almost entirely treeless. Their diaries tell us they used cottonwoods, which grow alongside rivers and streams, to build redoubts and dugout canoes—but the fields clotted with brush we see today did not exist.

Eastern red cedars—Juniperus virginiana, so not really cedars at all—are native but aggressive. In the absence of fire, they spread easily, turning grasslands into woods. We’re used to seeing them dotting the fields, but before the 1950s, this would have been a novel and shocking sight.

On a visit to K-State’s Konza Prairie Biological Station in the Flint Hills several years ago. I learned how under natural conditions fire raked the landscape and prevented trees from attaining much size. They showed us several demonstration beds used to study the effects of fire: one burned every year, one every three years, another five, and so on. The beds burned annually contained mostly native prairie grasses. The plots burned less frequently were in different stages of succession, with brushy plants like sumac and cedars establishing themselves.

In our area, lightning strikes and Native Americans started intermittent fires that tended to kill most young trees. Ones that survived, perhaps in part because they were already large enough to withstand the heat, often became landmarks for early settlers, rendezvous spots commemorated in place names like Lone Elm and Council Grove.

The end of an era: Dutch elm disease

I

It’s hard to imagine our landscape without the trees, but many of us have seen this firsthand and remember the feeling of devastation. In the 1940’s, Kansas City was full of marvelous trees—as Jackson County tax assessment photos show. Most were elms, and by all accounts they were magnificent.

Writer Gerald Shapiro, who grew up in Kansas City, describes their beauty:

All over Kansas City, elms were predominant — American elms, most of them, old and towering things, vase-shaped, luxuriant and stately, some of them a hundred feet tall. In summer, their graceful, leafy limbs bent down over streets and boulevards like dark green canopies, lending an air of grandeur even to sleepy middle-class neighborhoods like mine. When the leaves began to turn their autumn colors, they brought the whole river valley to fire.

“Just Before Dutch Elm Disease“

The elms may have been towering, but most probably weren’t more than fifty years old. In any case, Dutch elm disease arrived in Kansas City in 1957. Within ten years, the majority of the shade canopy had been wiped out. The beetle-borne fungus killed 70,000 trees, according to the Kansas City Star.

I remember visiting my grandmother in Kansas City in the late sixties, how bare it was, treeless, like the prairie she’d left. I think most of our present-day shade trees were planted after that time. But I wonder, were any of the large oaks in my neighborhood here before that?

The only way to find out for sure is to cut the tree down and count the rings, or take a core sample. However, formulas do exist for estimating a tree’s age.

Formula for estimating the age of trees

- Measure the circumference about 4.5’ above ground. (You will have to hug the tree.)

- Determine its diameter: divide the circumference by pi (3.14).

- Multiply the diameter by the growth factor as determined by species. How do you find the growth factor? This article includes a table: How Old Is My Tree?

- Make adjustments for conditions that affect tree growth. For trees in a suburban setting, the article recommends subtracting 25% from the total.

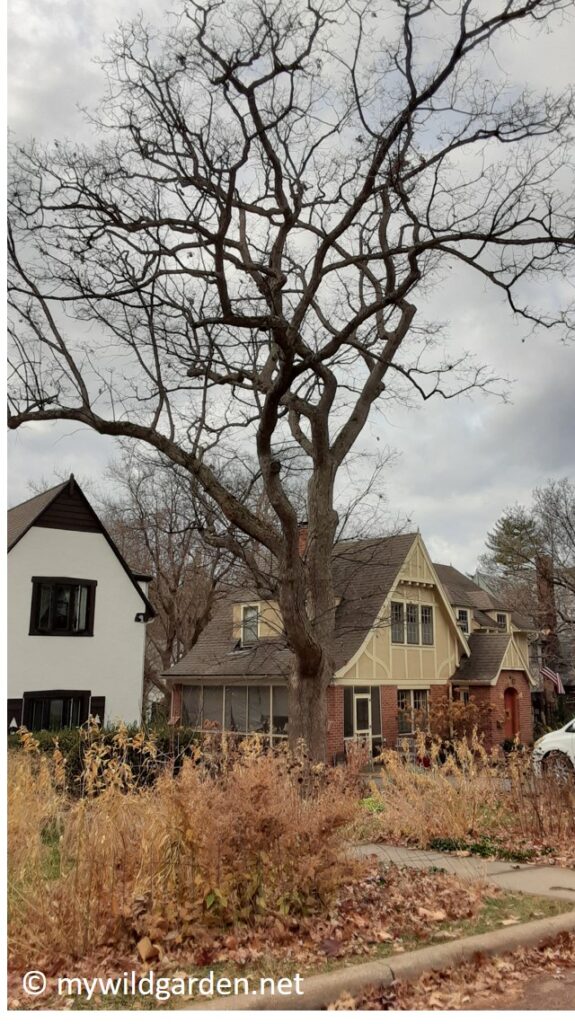

Example 1: Bur Oak

This large oak has a circumference of 117 inches. The formula estimates that it is 139 years old. (117″ ÷ 3.14 = 37. 37 x 5 = 185. 185 – 46 = 139)

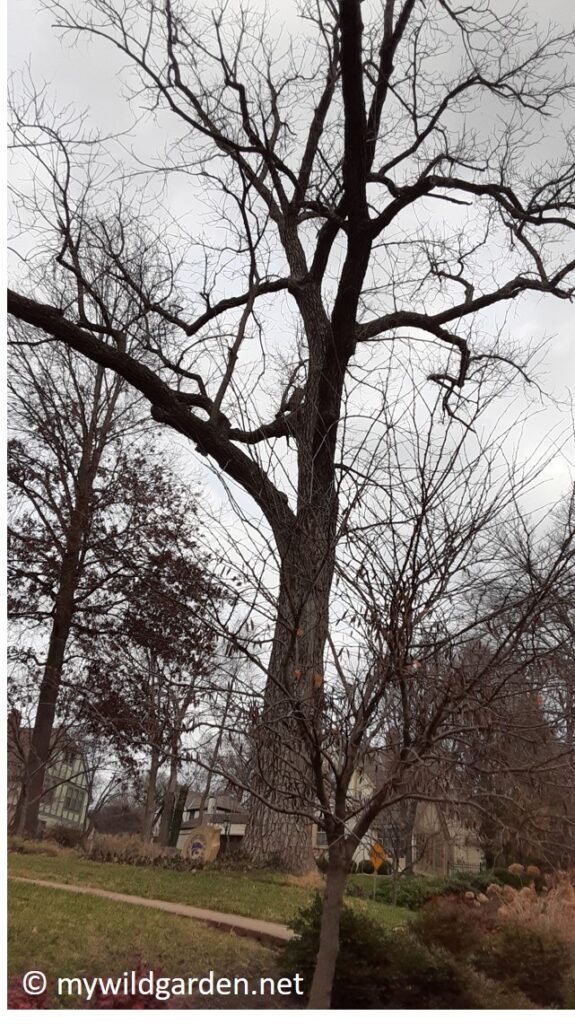

Maybe this isn’t a very good formula. This tree’s placement near the sidewalk suggests that it was planted at the same time as the house, in 1927, ninety-four years ago. Many similar trees grow nearby, as well as larger ones—like this one in Prairie Village in front of a house built in 1948, 73 years ago.

I think it’s likely these oaks were planted at almost the same time. The one in my neighborhood’s vertical growth pattern shows it was been forced to compete with other trees for sunlight. Both 94 and 73 are much younger than the formula’s estimate of 139, but no matter how many years they’ve been alive, they’re still impressive trees. The Kansas State Champion Bur Oak, estimated to be over 200 years old, has a diameter of 247 inches, so these have a ways to go.

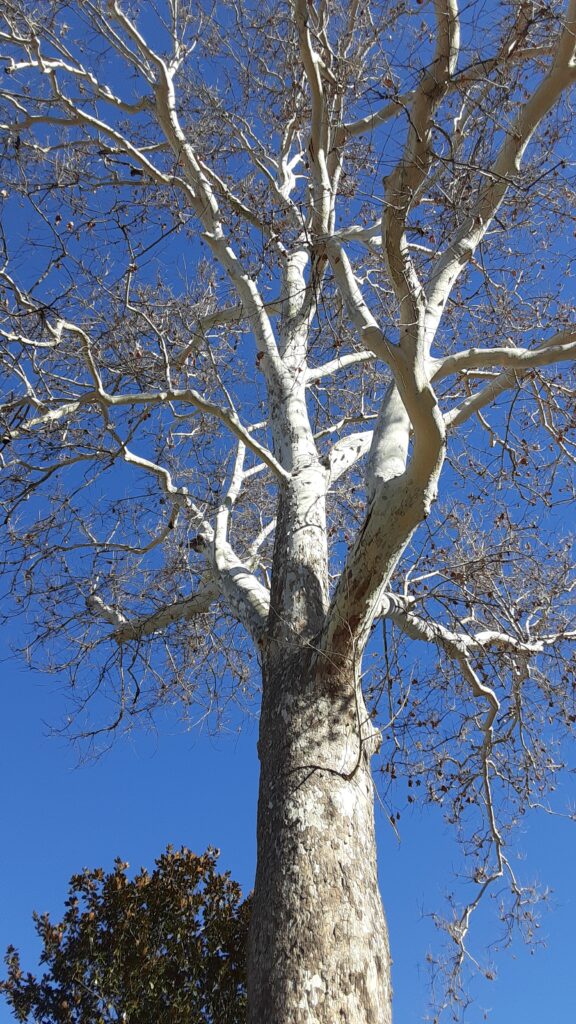

Example 2: Chinquapin Oak

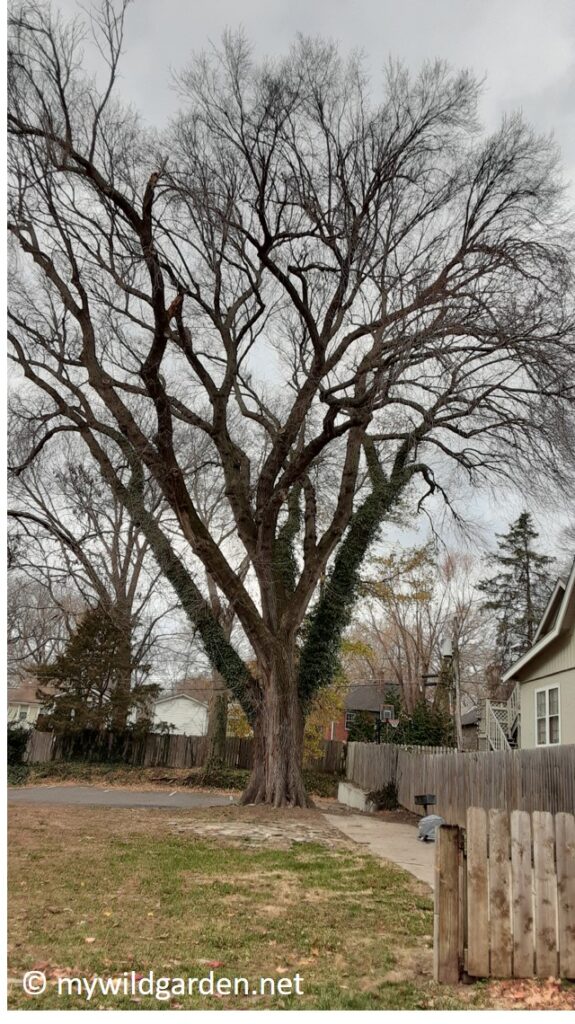

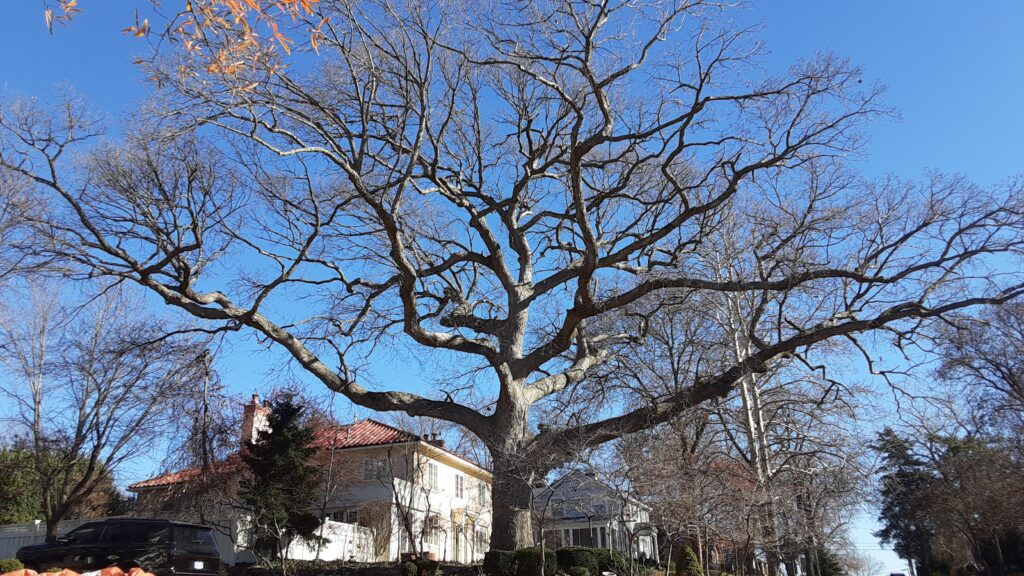

This enormous tree is unusual in the way its limbs stretch so widely, horizontal to the ground. It covers the entire lot. I believe it is a Chinquapin Oak.

- Circumference: 148 inches

- Diameter (DBH): 148” ÷ 3.14 = 47

- DBH x Growth Factor: 47 x 5.0 = 235

- -25%: 235 – 59 = 176

Could this oak really have started growing in 1845? I think that’s unlikely. After all, I’m using the same formula that was so obviously off on the other example. However, this tree may have been here pre-development. Many Bur Oaks grow in the neighborhood, but this is the only one of its type. It’s located on the lot line between two houses, not by the sidewalk. (When the trees are growing in a row, you can pretty much be sure a person planted them.) If this one is 176 years old, in 1923, when the subdivision was platted, it would have already been almost 80, so perhaps it was already impressive enough to warrant saving.

Unlike trees growing in forests and crowded neighborhoods, trees on the prairie don’t have to compete for light. This allows their branches to stretch out horizontally.

I think horticulturists would say this oak’s site is degraded. It’s no longer part of a community and natural regeneration is not possible. Few of its ecosystem functions remain intact. Nevertheless, it still provides many quantifiable benefits, and its magnificence is hard to deny. Each spring the Kansas City Parks Department hangs signs on trees that say how much money they save us, translating their value into dollars. This may be helpful to people who like to measure value that way. But it’s not the only way.

Learn more about oaks

These days, any conversation about oaks must mention Doug Tallamy, whose 2007 book Bringing Nature Home has done so much to raise awareness of the importance of native plants and insects. (No bugs, no birds!) He is passionate about the life-sustaining power of oaks.

Closer to home, this blog post by Brad Guhr at the Dyck Arboretum, A Grand Old Burr Oak, does a wonderful job explaining the history of oaks and their relation to fire. Oaks are resilient, hardy, and likely to withstand extremes as our environmental conditions change.

We’ve lost most connection with phenomena that transcends generations. Artificial light makes it impossible to see the stars. I don’t recognize or know the names of the constellations. The natural features of the landscape have been altered. I orient myself using manmade objects, streets and houses. If those suddenly vanished, I would be completely lost. Both of these trees were growing before most of us were born, and both are likely to outlive everyone who is alive on the earth today. I find that fascinating.

Thanks for reading!

This is the first of three planned posts focusing on aspects of our landscape in winter. Did you enjoy it? What are your thoughts about Kansas City trees? Please let me know! Look for my next winter post in mid-January 2022.

References

https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/ks/newsroom/features/?cid=nrcseprd468806

https://kpbs.konza.k-state.edu/

https://kchistory.org/digital-collections

https://www.ksre.k-state.edu/historicpublications/pubs/SB434.pdf

https://www.kansascity.com/news/special-reports/doomsday_kc/article27385219.html

https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2226&context=cutbank

https://www.purduelandscapereport.org/article/how-old-is-my-tree/