Last week I visited the conservatory at Powell Gardens and spoke with Brent Tucker, the horticulturist who designed the holiday display. I’ll talk about their colorful mix of poinsettias and other tropical plants in another post. In the meantime, our visit got me thinking about conservatories and their purpose—and about orangeries, glass houses, hot houses, and greenhouses.

At one time these words may have denoted different things: an orangery was a free-standing structure for growing fruit; a heated conservatory conserved tender plants. However, over the years these distinctions have been lost, and now we use these terms pretty much interchangeably. Whether practical or decorative, free-standing buildings or sunrooms, these structures exist to alter the normal range of seasons and protect tender plants during winter.

For me, the term conservatories conjures pictures of wealthy Europeans cultivating tropical exotics from the colonies—Elizabeth Bennett and Mr. Darcy walking down a gallery at Pemberley lined with glittering panes. Turns out, I’m not far off the mark.

The history of conservatories parallels the history of window glass, and also of wealth and fashion. Greenhouses have been around forever—the Romans had greenhouses—but early ones weren’t glass. Roman greenhouses were basically frames built over the plants and covered with cloth or selenite. In the medieval times, ordinary people covered their windows with wood shutters or animal skins. By Shakespeare’s day, glass windows were becoming more available, but they didn’t look like contemporary windows. Often opaque, they were made of something called crown glass, which looked like the flattened bottoms of bottles.

Innovations in glass-making technology in the mid-1600’s allowed for the production of panes. Around the same time, growing orange trees became fashionable in France, Germany, and the Netherlands. In the UK, one of the earliest surviving orangeries dates from the 1670’s. Ham House in Surrey is a solid-looking brick building with long line of large, south-facing windows. Before it was built, gardeners planted the orange trees in tubs, which they covered in winter. After the orangery was built, they moved the orange trees inside and out depending on the seasons.

Some orangeries, like the greenhouse designed by George Washington at Mt. Vernon, had in-floor heating systems warmed by fire. This is a good video.

Monticello also had a garden room attached to the house, which Jefferson called the South Piazza. Apparently, he had difficulty heating it and his plants often died. (Thanks to my friend Michael Ray for this photo.)

The enthusiasm for oranges that swept Europe in the 17th century is hard to imagine now that every grocery store in the country stocks them year-round. When my brother and I would find them in our Christmas stockings, we scorned them for taking up valuable space. But our grandmother, who grew up on an Iowa farm in the early 1900’s, described how exciting it was to get oranges from Florida at Christmas. They must have seemed miraculous.

Built in the early 1700’s, the ornate Orangery at Kensington Palace was used for ceremonies and entertaining, as well as growing plants. Considered a significant and influential building, it has a slate roof, which limits the amount of light and makes it impossible for some tropical specimens to thrive. Technological advances in glass and cast iron during the Victorian era allowed for the construction of glass roofs, like this one on the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory at the New York Botanical Garden.

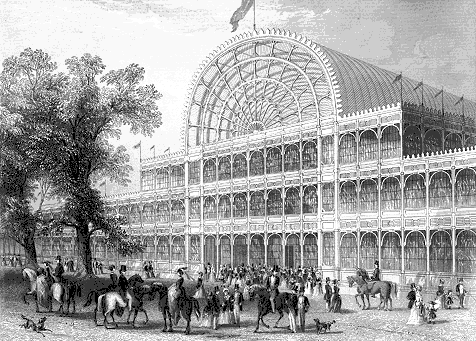

Cast-iron frames supported curved glass roofs like the one at the Crystal Palace, perhaps the world’s most famous conservatory, designed by Joseph Paxton in 1851.

The Crystal Palace was constructed from millions of standard-sized panes, a decision which lowered costs and sped up the pace of construction. Unlike anything people had ever seen before, the structure had “the greatest area of glass ever seen in a building. It astonished visitors with its clear walls and ceilings that did not require interior lights.”

When fire destroyed the Crystal Palace in 1936, 100,000 people turned out to watch it burn.

If this subject interests you, you’ll love this article, A history of glasshouses, orangeries and potting sheds, from the UK National Trust.

The conservatory at Powell Gardens is one of the few currently open to the public in Kansas City, perhaps the only one as the orangery at Kauffman Gardens remains closed because of COVID. (The rainforest exhibit at the Kansas City Zoo could be considered a conservatory.) Unlike historic orangeries, which are oriented to the south, the Powell Gardens conservatory depends on pyramid-shaped roof to let in light.

Conservatories and greenhouses create a world within a world, a tropical rainforest under glass. Visiting them can be magical. I love going swimming on a snow day, enjoying the damp, humid air while white snow piles up against the windows. It’s fun, like wearing rain boots and stomping in a puddle. Even though I’m drawn to gardens that express authenticity and a sense of place, I love the way conservatories bring the outside in, all year round. Like an aquarium or the zoo, they nurture living treasures, educate us, and stimulate our curiosity. They transport us to another world.