Today I spoke with Dana Posten about the wonderful pollinator garden she has developed with her husband Mike. Our conversation was as wide-ranging as their gardens, which include a cutting garden, fruit trees, and private potager. We talked about far too much to cover in one post, so today I’m going to focus on the pollinator garden, which is visible to passers-by.

The Postens began working on the gardens six years ago when they bought their house on its distinctive wedge-shaped lot. After removing some foundation plantings and ailing trees, they turned their attention to creating what Posten calls a “formal pollinator garden.” This eye-catching triangular bed looks wild in some ways, but on closer inspection reveals its symmetry and organization.

About the bee house, Posten says, “That’s coming down.” Bee houses look charming, but as she points out, pre-fab ones can be associated with problems and may harm bees more than help them.

Three redbuds define the area, each surrounded by evergreen boxwoods. Two large masses of amsonia (bluestar), an early blooming perennial, grow on each side. Between these grow silvery munstead lavender and germander, which Posten describes as “bee crack. They shiver with activity.”

This early image of the bed shows its distinctive shape, as well as how the garden has evolved.

The bed contains many other plants, including monarda, rue, solidago, milkweed, and others. All are nectar sources for bees and butterflies.

It’s striking how many different varieties of plants are growing in this small area. (Posten is impressively knowledgeable about plants—she loves researching them). Many are native, but not all. Some are less-commonly seen varieties of familiar species, like this gymnocarpus physocarpa (hairy balls milkweed).

The diversity is dazzling, but the effect is still harmonious, thanks to rhythm and repetition of color and shape, and the consistent theme of supporting pollinators. Defined paths delineate the beds and prevent them from looking chaotic.

A sign in the corner identifies this pollinator garden as a certified Monarch Waystation. Monarch Watch, a program based at KU, helps raise awareness about the dwindling numbers of monarchs caused by loss of habitat and pesticides.

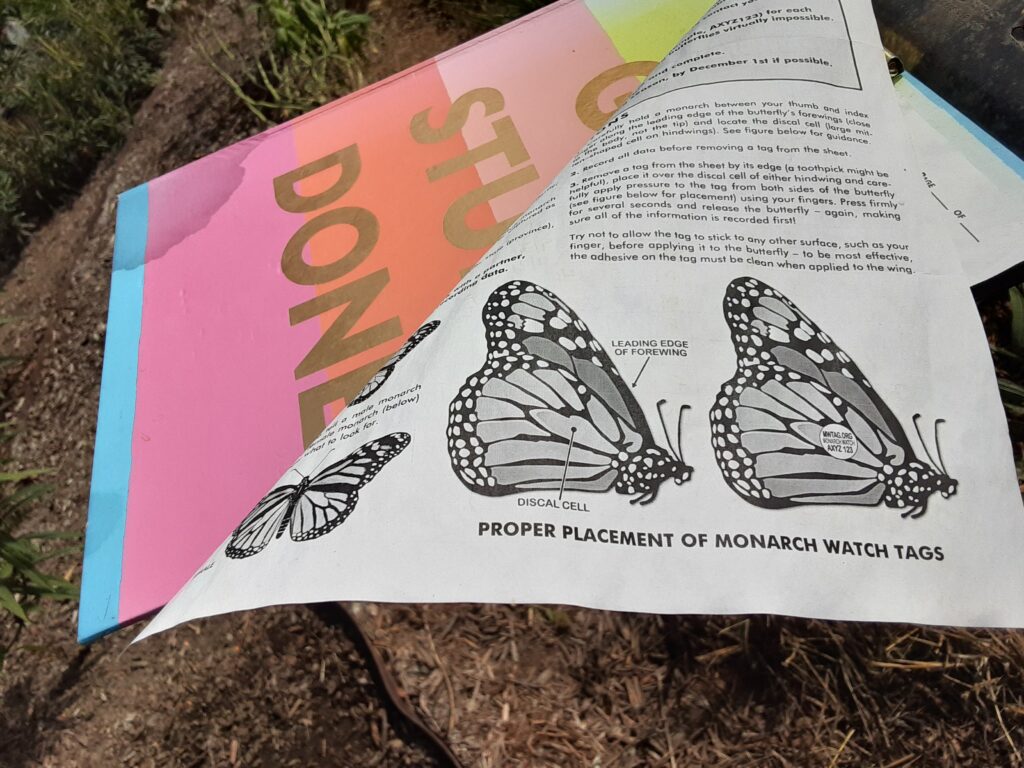

Certifying your garden can help save the monarchs. All you have to do is verify that you have host and nectar plants and follow sustainable management practices. Gardeners also help by tagging butterflies to provide scientists data about how populations are faring. The monarch’s annual migration is in full swing right now, and several fluttered by as we talked.

First catch the butterfly safely

Affix a tiny sticker to its wing

Release it, then note the date, location, gender, and tag number on the Monarch Watch sheet

Programs like Monarch Watch have helped make a difference: monarch numbers in 2019 increased by 144 percent over the previous year, according to the Center for Biological Diversity. So thank you, everyone who grew milkweed, myself included!

Sadly, monarchs on the west coast haven’t fared as well, with numbers dropping from 1.2 million in 2000 to fewer than 30,000 last year.

A more recently planted area on the west side of the property features several different types of native grasses and wildflowers. After seeing the plantings on the High Line in New York and the film Five Seasons: The Gardens of Piet Oudolf, the Postens were excited by the potential of using native grasses in a new way. They used soil solarization to prepare the beds, covering them with plastic last summer through the winter to smother germinating weeds and kill off Bermuda grass. This strategy is an alternative to using glyphosate, or Roundup, which they strenuously dislike, believing it serves no purpose. Many of these plants, planted as bare roots in April, are now flourishing. Some are even blooming now, such as kniphofia uvaria (red-hot poker or torch lily), and liatris (blazing star).

As Posten points out, in reality grasses grow differently here than in Oudolf’s gardens: “Some may grow to be much larger, while others may not grow at all. Conditions here are just so different.” Lush meadow plantings are difficult to reproduce in small suburban yards. However, grasses can still evoke an atmosphere inspired by Oudolf’s gardens and principles. Seeing this planting in its first year is of particular interest to a novice like me, and helps me visualize what the plants look like in the ground and how far apart to space them.

I’ve never seen a private garden quite like this. Bees and butterflies must be thrilled to discover it, and people get excited about it, too. Posten says, “Everyone can find something to like.” This is great to hear, because intermingled plantings are complex and can be difficult to “read.” Our notions of what’s beautiful are mostly learned, and the unfamiliar can feel strange. The delight we feel seeing this garden—its very existence—may signal ways our priorities are evolving. Perhaps we’re becoming more willing to take our ecological concerns seriously, and open to considering new ideas of beauty.

More beauty. Everyone deserves that!